- Home

- R. A. Spratt

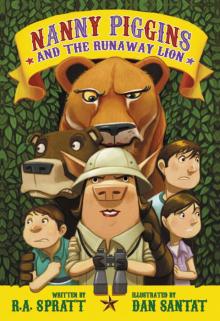

Nanny Piggins and the Runaway Lion

Nanny Piggins and the Runaway Lion Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Copyright Page

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitutes unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

PREVIOUSLY ON NANNY PIGGINS…

IF YOU HAVE JUST PICKED UP THIS BOOK AND are wondering—Who are these characters? What’s been going on? How can a pig be a nanny?—do not be daunted.

All you need to know is that Nanny Piggins (the world’s most glamorous flying pig) ran away from the circus and came to live with the Green family as their nanny. The children, Derrick, Samantha, and Michael, fell in love with her instantly. Who could not love a nanny who thinks that the five major food groups are chocolate, chocolate, chocolate, more chocolate, and cake?

The Green children are lovely, normal children. Derrick can be a little scruffy and grubby, but then, isn’t that true of all eleven-year-old boys? Samantha does tend to worry, but nine-year-old girls who mysteriously lose their mothers in boating accidents would be silly not to be concerned. And Michael is an uncomplicated, happy soul who shares his nanny’s enthusiasm for high-sugar food.

Before long Nanny Piggins’s adopted brother, Boris, the dancing bear, came to live in their garden shed (unbeknownst to Mr. Green, the children’s father).

There are other recurring characters—a silly headmaster, a perfectly perfect rival nanny, thirteen identical twin sisters, a besotted School District Superintendent, and a wicked Ringmaster, just to name a few. But trust me, you will pick all that up as you go along.

The only other person you need to know about is Mr. Green. He is not happy about having a pig for a nanny, or having children generally. Secretly he would like nothing more than for Derrick, Samantha, and Michael to disappear into thin air, perhaps as part of a conjuring trick. But he realizes that is unlikely, although not impossible, because it is essentially what happened to their mother, Mrs. Green, on one very unfortunate boating trip.

Mr. Green did try to remarry in an effort to get rid of Nanny Piggins and palm his children on someone else, but that proved disastrous. (For further details, see Nanny Piggins and the Wicked Plan.) So as this book begins, Mr. Green is cooking up new schemes to make himself childless.

Yours sincerely,

R. A. Spratt, the author

To Mum and Dad

R. A. Spratt and Nanny Piggins would also like to thank…

Connie Hsu

Chris Kunz

Elizabeth Troyeur

the wonderful librarians of America and

the great indefatigable children’s lit pusher of Los Angeles, Lindy Michaels

CHAPTER ONE

Nanny Piggins and the Foreign Exchange Student

an anyone remember what the figurines looked like?” asked Nanny Piggins.

“All I can remember is that they were ugly,” said Boris.

Nanny Piggins, Boris, and the children were in the living room looking at the shattered remnants of the late Grandma Green’s figurine collection. The ten miniature statues had accidentally been smashed in a particularly athletic game of charades. (Nanny Piggins had set a vase of flowers on fire when acting out the book title The Bonfire of the Vanities. Then she had to leap to safety before her hair was caught in the inferno.)

“I think one of the figurines was a woman with a dog,” said Michael. As a seven-year-old boy, he naturally had an affinity with dogs.

“I’m pretty sure those green parts were a mermaid,” said Derrick, who, as an eleven-year-old, was developing an eye for mermaids.

“And one was a milkmaid with a cow… or a goat… but definitely something you milked,” added Samantha. Being a nine-year-old who worried a lot, she did not like to commit to a decision.

“I know what we can do,” said Nanny Piggins. “Let’s recombine all the pieces to make one giant figurine of a monkey!”

“Why a monkey?” asked Boris.

“Everyone likes monkeys,” said Nanny Piggins.

The others nodded at the truth of this statement.

“Which just goes to show,” continued Nanny Piggins, “you can scratch yourself, slap your head, and bite tourists, but if you do it with enough charm, people will still think you’re adorable.”

So they set to work. Nanny Piggins was extremely good with superglue. When you smashed as many Ming vases as she had in her time, you needed to be. They had just reached the point where all ten of their hands were required to hold everything in place while the glue set when Mr. Green walked into the room.

“Wah!” said Boris as he ducked under the table. Then “Ow!” as he realized he had just ripped out a chunk of fur because he had accidentally superglued his paw to the figurine. Fortunately Mr. Green did not notice the ten-foot-tall dancing bear hiding under the table, because he was a very unobservant man. And the brain tends not to process information that is impossible to believe.

“Hello, children,” said Mr. Green.

They all immediately knew something terrible was wrong because Mr. Green usually never spoke to the children except to tell them to “Go away” or “Be quiet” or “Stop pestering me for lunch money.” Also, he was smiling, a skill he was very bad at. Mr. Green’s smiles were frightening. Like a baboon baring his teeth right before he poops on his hand and throws it at you.

“Hello,” said Nanny Piggins conversationally. “We were just polishing your beloved figurine. What do you think?”

Mr. Green leaned forward and peered at it. They all held their breath as they waited to see if he would notice the difference between the ten original figurines and the giant one they were now holding.

“It looks fine,” said Mr. Green.

They sighed with relief.

“But…” he continued.

They held their breath again.

“Has it always been furry?” Mr. Green asked, looking at the brown tuft now stuck to the monkey’s neck.

“Oh yes,” said Nanny Piggins. “Embedded bear fur is the signature mark of a genuine antique Staffordshire flatback.”

“Really? Well, my mother had quite the eye,” said Mr. Green proudly. (It is funny how people grow fond of the relatives who once terrified them after they are safely dead.)

“Don’t let us keep you from your tax law work,” hinted Nanny Piggins as she politely tried to get rid of Mr. Green. “I know you must have something dreadfully important to do in your office. Paper clips to straighten and rebend, or some such.”

This comment slightly unnerved Mr. Green because that was exactly what he had spent four hours doing only that morning, and then billed the time to a rich, old widow who was too nearsighted to check her invoice.

“Oh, no, I came in here to make an announcement,” he said. “You children are very lucky.”

The children groaned. They knew something terrible was coming if their father thought they were lucky.

“What have you done?” Nanny Piggins glowered, suspecting him of trying to sell them for medical experiments again. “The hospital told you clearly. They don’t accept donated organs from living people.”

“No, this is another, even better, idea. I’ve arranged a wonderful educational opportunity for the three of you,” continued Mr. Green. He really was beginning to look very smug.

“What sort of wonderful educational opportunity?” asked Nanny Piggins, bracing herself to launch, teeth-first, at his leg.

“Well, you see, a fellow at work was telling me about his son and how he sent him away as an exchange student,” said Mr. Green.

“And how does that affect Derrick, Samantha, and Michael?” asked Nanny Piggins suspiciously.

“I thought it sounded like such a good idea I’ve enrolled them in an exchange-student program!” said Mr. Green triumphantly, whipping the paperwork out of his pocket and waving it in their faces. “It’s all arranged. By the end of next week, they’ll be off to Nicaragua for six months.” Mr. Green was positively glowing with happiness. The idea of six months without his own children pleased him immensely.

“But I don’t want to go to Nicaragua!” protested Nanny Piggins. “I’ve been there twice already, and while the turtles are nice and gallo pinto is delicious, the humid weather makes it very difficult to do anything with my hair.”

“You won’t be going,” said Mr. Green.

“But what will Nanny Piggins do while we’re away?” worried Samantha.

“Find a new job, of course,” said Mr. Green.

“Noooooo!” yelled Michael. Being the youngest, he was more prone to outbursts of emotion. He would have flung himself at his father in a rage, but, like Boris, he had accidentally glued his hands to the figurine.

And Derrick tried to kick his father’s shin under the table. Unfortunately, as he was only eleven years old, his legs weren’t long enough to reach.

“I’m sure Miss Piggins will find work somewhere else,” said Mr. Green. “Perhaps”—he started to laugh here as though he had thought of something funny—“perhaps she can get a job”—again he actually chortled—“in a bacon factory.”

The children gasped and Boris banged his head on the dining table as he flinched away in horror. There was no greater insult to a pig than to mention the word bacon. Mr. Green’s idea of a joke had mortally offended Nanny Piggins. If it were not for the fact that she, like Michael and Boris, had too much superglue on her trotters and was now stuck to the figurine, Mr. Green would have been in terrible trouble. As it was, she dragged the giant figurine three feet across the table as she lunged toward him.

Mr. Green cowered away. “It is all legitimate. Lots of parents do it. It’s educational,” he protested, the way people always protest when they have done something very bad and are about to be punished for it.

“I suggest you leave the room now, Mr. Green,” said Nanny Piggins, “to allow the children and me time to control our emotions.”

Emotions of all varieties scared Mr. Green, so he did as he was told. He scuttled away and drove back to the office.

“What are we going to do?” wailed Samantha. She was not normally given to wailing, but the prospect of six months in Nicaragua can have that effect on a girl.

“Obviously we will have to thwart your father,” said Nanny Piggins. “It really is exhausting putting him in his place all the time. I wonder if we got him a futon whether we could persuade him to sleep in his office and never come home.”

“Do you have a plan?” asked Michael hopefully. He would actually have quite liked to go to Nicaragua because he was an adventurous boy who was, of course, intrigued by turtles. But he did not want to be separated from Nanny Piggins. She was the only family the children had. If you did not count their father. And none of them did.

“I have the beginning of an idea,” admitted Nanny Piggins as she thoughtfully rubbed her snout. (She had to rub it on her arm because, of course, her trotters were glued to the figurine.)

“What do we have to do?” asked Derrick, desperate to take some sort of action.

“Well, for a start, we have to resmash this figurine,” said Nanny Piggins.

“To teach Father a lesson?” asked Samantha.

“That is an added benefit. But the main reason is because we’re all stuck to it. And I’ve run out of nail polish remover, so I’ve got nothing to dissolve the glue,” said Nanny Piggins.

So after smashing the figurine back into a thousand pieces, and leaving it there because Mr. Green did not deserve to have it refixed, the children went off to school. Nanny Piggins assured them that she would soon solve the problem. Two weeks was a lot of time. She was sure to think of something.

The family was sitting around the breakfast table the next morning, which was not a pleasant experience for Mr. Green. He kept getting hit in the head with slices of toast. Michael claimed they were slipping out of his hands when he buttered them, but Mr. Green suspected that his youngest son might have been throwing them intentionally. Suddenly, there was a knock at the front door.

“Who could that be?” demanded Mr. Green.

“I expect it is someone at the front door,” explained Nanny Piggins slowly and clearly. “They probably want you to open the door and speak to them.”

“One of you children go,” said Mr. Green dismissively.

“The children shouldn’t answer the door to strangers,” chided Nanny Piggins.

“Then you answer it,” said Mr. Green.

“Very well,” said Nanny Piggins, primping her hair as she got up from the table. “But if it is someone important who has come to give you a medal for services to tax law, are you sure you want the door to be answered by a pig, even if she is the most glamorous pig in the entire world?”

“All right, I’ll do it myself,” grumbled Mr. Green. As far as he was concerned, the fewer people who knew he housed a pig the better. Little did he realize, however, that while a great number of people knew Nanny Piggins lived in the house, almost no one knew (or cared) whether Mr. Green even existed.

Nanny Piggins and the children followed him, curious to see who would pay Mr. Green a visit at breakfast time.

Mr. Green flung open the front door. “What do you want?” he demanded rudely. Then he immediately had to look down because the person he was being rude to was two feet shorter than he was expecting.

“Bonjour, Monsieur Green,” said the diminutive boy standing on the doorstep. “My name is François. I am eleven years old and from Belgium. And I am to be your exchange student. It is a great pleasure to be welcomed to your country!” François then reached up, grabbed Mr. Green’s head, pulled him down, and kissed him once on each cheek.

Mr. Green practically went into shock as François picked up his little suitcase and entered the house.

“Bonjour, I am François,” François said to Nanny Piggins and the Green children.

“Bonjour,” said Derrick, Samantha, and Michael.

“Thank you for welcoming me into your home,” continued François with impeccable politeness and a lovely little bow. “I look forward to immersing myself in your culture.”

“What does ‘immerse yourself in culture’ mean?” Michael whispered to Derrick.

“I think he wants to dip himself in yogurt,” Derrick guessed.

“Now just you wait here,” spluttered Mr. Green. “What is the meaning of this? Coming into my house with a suitcase and speaking French. It just isn’t acceptable.”

“But you are Mr. Green, yes?” asked François, looking just the right amount of confused and hurt to make even Mr. Green feel slightly guilty for raising his voice.

“Well, yes,” admitted Mr. Green, secretly wishing he was not.

“And you signed up to join the Friends Around the World exchange-student program, did you not?” François asked.

“He did indeed,” said Nanny Piggins. “We all saw the paperwork yesterday.”

“Yes, but that was to send my children away,” protested Mr. Green.

“Of course,” said François. “But before your children go, you must first host a student in your home. That is the way the system works. Didn’t you read the fine print of the contract?”

Mr. Green had not. Which was unusual because he was a lawyer and it was his job to write fine print into contracts. So he should have known better than anyone how devious fine print can be. But when he was at the exchange-student office, he had been so euphoric at the idea of six months without his chi

ldren he had been too giddy for reading. Instead he had been busily fantasizing about closing up the children’s bedrooms and saving money by disconnecting the electricity to all but one room in the house.

“How long are you going to be here?” asked Mr. Green, beginning to accept that perhaps there was no way out of this predicament. “Not six months, I hope.”

“Non, non, non,” said François (which is French for “no, no, no”). “I will be here for twelve months. I am on the advanced program.”

“Twelve months!” exclaimed Mr. Green, truly aghast. “But what am I supposed to do with you?”

“Just treat me as you would your own children,” said François.

“He’s going to wish he stayed in Belgium,” predicted Michael under his breath.

Mr. Green would have dearly loved to send François packing, but after fetching the contract and reading the fine print three times, he realized he could not. If he wanted his children to go to Nicaragua, he had to host the Belgian boy. But Mr. Green reasoned that one foreign child had to be better than three of his own (it was just a case of simple mathematics to his mind), so he decided to stick to his decision. Once Derrick, Samantha, and Michael were safely in Nicaragua, perhaps there would be some way he could lend François out to a sweatshop or a chimney-sweeping service or some such.

The next few days proved very interesting. François was a polite, charming little boy who went to his own international school in town. So he was no bother for Nanny Piggins, Boris, and the children at all. But for some reason, he was fascinated by Mr. Green.

He kept muttering things like, “Sacre bleu! (which is French for “Wow!”) We have no one like this in our country.”

Every time Mr. Green slurped his soup, picked his nose, or dug the wax out of his ear, François would be there taking notes and even drawing diagrams, which he would then delightedly take and show the other children.

“Observe your father. He is a most fascinating man,” exclaimed François.

The Final Mission

The Final Mission Stuck in the Mud

Stuck in the Mud Near Extinction

Near Extinction Bitter Enemies

Bitter Enemies No Rules

No Rules The Mystery of the Squashed Cockroach

The Mystery of the Squashed Cockroach The Plot Thickens

The Plot Thickens Nanny Piggins and the Accidental Blast-off

Nanny Piggins and the Accidental Blast-off Friday Barnes 2

Friday Barnes 2 Nanny Piggins and the Pursuit of Justice

Nanny Piggins and the Pursuit of Justice Nanny Piggins and the Race to Power 8

Nanny Piggins and the Race to Power 8 Nanny Piggins and the Wicked Plan

Nanny Piggins and the Wicked Plan Nanny Piggins and the Daring Rescue 7

Nanny Piggins and the Daring Rescue 7 Friday Barnes 3

Friday Barnes 3 Danger Ahead

Danger Ahead Nanny Piggins and the Runaway Lion

Nanny Piggins and the Runaway Lion The Adventures of Nanny Piggins

The Adventures of Nanny Piggins