- Home

- R. A. Spratt

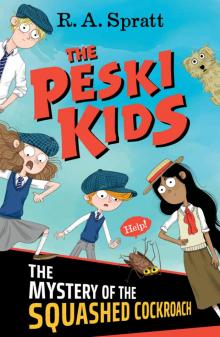

The Mystery of the Squashed Cockroach

The Mystery of the Squashed Cockroach Read online

About the Book

Life is hard enough without having to spend time with your siblings. But there is no other way for Joe, Fin and April Peski to solve the mystery of the cockroach catastrophes that is rocking their new home town of Currawong.

Along with Loretta, their stunningly beautiful yet sociopathic next-door neighbour, and Pumpkin, the world’s worst trained dog, they set out to catch the culprit.

Together they are The Peski Kids.

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1: A BAD START

Chapter 2: WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Chapter 3: DAD

Chapter 4: SCHOOL UNIFORM

Chapter 5: THE NEW SCHOOL

Chapter 6: NOT FITTING IN

Chapter 7. JOE AND THE BOWLS

Chapter 8: DO OVER

Chapter 9: THE FIRST HURDLE

Chapter 10: SOMETHING IN THE BUSHES

Chapter 11: KITTY-CAT BANDAIDS

Chapter 12: PAPER, ROCK, GLASS

Chapter 13: SOMETHING SERIOUS

Chapter 14: THE INVESTIGATION BEGINS … BADLY

Chapter 15: SERIOUSLY

Chapter 16: AT HOME

Chapter 17: FRAMED AGAIN

Chapter 18: CONFRONTATION WITH A BEAUTY

Chapter 19: SOMETHING IN THE GARDEN

Chapter 20: TALKING TO GIRLS

Chapter 21: THE BALL

Chapter 22: DEPRESSED

Chapter 23: THE COCKROACH RACES

Chapter 24: EVERYTHING GOES WRONG

Chapter 25: THE CHASE

Chapter 26: THE KEY

Chapter 27: HOME IS WHERE THE DISASTER IS

About the Author

Books by R. A. Spratt

Friday Barnes

Nanny Piggins

Imprint

Read more at Penguin Books Australia

To Violet and Samantha

The line shuffled forward. Dr Banfield had just checked in for her flight. She was hoping to get back before the children came home from school. She only needed to pass through security, then she would be able to sit down and relax in the lounge, as much as you can relax surrounded by a thousand sweaty, nervous strangers. But the line was taking forever.

There was a family in front of her fussing over their hand luggage. They seemed to have broken every airport security rule – liquids, scissors, bottle openers. They had everything they shouldn’t in their bags.

Finally, their things passed through the X-ray machine for the last time and Dr Banfield was able to lift her one carry-on suitcase onto the conveyor. She rifled through the pockets of her old tweed jacket, digging out her spare glasses, throat lozenges and tissues. She dropped them into a plastic tray, then stepped through the metal detector.

Security guards never wanted to pat her down or do an explosive test on her bag. She was a frumpy middle-aged lady. She was harmless. They barely even noticed her. That was, until now. The conveyor belt juddered to a halt. Dr Banfield looked up as a man in a cheap grey suit stepped into the security area. He whispered something to the X-ray operator, then pulled Dr Banfield’s suitcase aside.

He motioned for Dr Banfield to join him at the counter. This had never happened to her before. She watched as the man in the suit opened her suitcase and searched through her dirty clothes and museum paperwork.

‘What’s this?’ asked the man, with a thick accent. He pulled something out from the bottom of the suitcase. It was a large bone.

‘The ulna of a stegosaurus,’ said Dr Banfield. ‘It was found in Kiev. It is particularly significant because the striations on the bone appear to be the teeth marks of a sabre-toothed tiger, which would be the earliest known confirmation of that species on the Asian continent.’

‘Really?’ said the man in the suit. ‘We’ll see about that.’ He raised the bone and whacked it down hard on the edge of the counter.

‘No!’ cried Dr Banfield. ‘It’s a crucial fossil for understanding the evolution of mammals in Eastern Europe.’

The man in the suit apparently did not like being yelled at by a frumpy middle-aged lady. He looked angry now as he raised the bone again and smashed it down even harder. It shattered into a thousand fragments, but lying in the middle was something black and shiny. A small USB drive.

The man in the suit picked it up. ‘What do we have here?’

‘I’ve got no idea how that got there,’ said Dr Banfield. She turned pale. Her eyes gaped wide. This was going terribly wrong.

‘You’d better come with me,’ said the man ominously.

‘But my flight?’ said Dr Banfield. ‘I have to get home. My children are expecting me.’

‘I’m sure it will only take a few moments to clear this up,’ said the man with a smile.

He was lying. It took Dr Banfield’s very large brain just a millisecond to recognise this fact, another millisecond to see that two armed guards were approaching to assist him and a third millisecond to decide that her best course of action was to punch this man, in his cheap grey suit, in the throat with her wedding ring.

Dr Banfield lashed out with lightning speed, hitting the man so hard his brain was momentarily starved of oxygen and he collapsed. The two armed guards hesitated. Their smaller brains were struggling to assimilate the fact that a dowdy middle-aged lady had just felled their department head. One of them belatedly reached for his gun, but his hand had only touched the grip when Dr Banfield broke both the bones in his forearm with a brutal turning kick. She then kicked him in the knee with her other foot to knock him down too.

The other guard lunged for her. Dr Banfield ducked, slammed her elbow into his solar plexus, delivered an uppercut to his jaw and took off running.

She vaulted over the X-ray machine and sprinted back out into the check-in lobby. It would take a few seconds for reinforcements to arrive. She had to get out of there. Unfortunately, 2 pm at any airport is a busy time. People were moving slowly, dragging unwieldy luggage behind them.

Dr Banfield ran, picking up speed as she hurdled bags, bounced off passengers and dodged around trolleys, until suddenly she slammed into a brick wall. At least, that’s what it felt like. She soon worked out from the grey polyester jacket pressed into her face that she had been crash-tackled. She was hoisted to her feet. The man in the suit was holding her tightly by the upper arm. He looked dishevelled.

‘Dr Banfield, you are under arrest,’ spat the man.

‘But I’m just an academic,’ said Dr Banfield, with bumbling innocence. ‘A scientist. I study dinosaur bones.’

‘Don’t give me that,’ said the man. ‘You are a spy.’

‘Shut your face or I’ll shut it for you,’ said April angrily. She was a wiry girl who, like a hummingbird, had the strange ability to be in constant motion and appear eerily still at the same time.

‘You can’t shut a face,’ said Fin, in his pedantic monotone. ‘A face isn’t something that opens and closes. You could ask me to shut my eyes or my mouth, but my ears and my nose are unblockable orifices.’

‘I’ll block them for you,’ said April, ‘when I punch you and they swell shut.’

Fin narrowed his eyes slightly, which was about as expressive as his features got. He was not terribly in touch with his own emotions, so they rarely affected the shape of his face.

‘N-no violence,’ said Joe, their older brother. He stammered when he was nervous and talking made him nervous, so he stammered quite a lot. Joe knew exactly what he wanted to say, but just as the words were about to leave his mouth they would perform some sort of acrobatics on the tip of his tongue and refuse to e

merge. So generally he said very little, except for constantly reminding April and Fin not to hurt each other.

April made a scoffing noise. Their mum didn’t often notice what was going on so it was pretty easy to keep things from her, like kidney-punching your brother during dessert.

April made do with shoving Fin out of the way and stomping up the front path so she got to the door first. She punched in the code. They lived in a normal suburban house, but their mother was forgetful and often lost her keys, so they’d had a pin-pad lock installed. There is a limit to how many times you can get locked out of your own home and it still feels fun. That limit is one. Having to eat raw vegetables from the garden while you wait for a locksmith is never a barrel of laughs.

As soon as they pushed into the house a whirlwind of fur leapt at April, trying to lick her face but falling short and scrabbling all over her knees instead.

‘Ooh, I missed you too, Pumpkin,’ gushed April, bending over to greet her beloved dog. ‘I hate it when we do javelin in PE and you have to stay home.’

Pumpkin’s head snapped round as Fin entered the house. The dog leapt forward and bit him on the ankle.

‘Ow!’ cried Fin.

‘Good boy,’ said April, fishing a treat out of her pocket and rewarding her dog.

‘You can’t train Pumpkin to bite me,’ said Fin.

‘I didn’t train him,’ protested April. ‘He’s just following his natural canine instincts. He can smell loser.’

Joe was a tall, and growing taller, sixteen-year-old boy. He seemed to have more muscles popping up every month, so he spent a great deal of time eating food. He left April and Fin to their argument and went into the kitchen to find a snack. He didn’t have much luck. The fridge was empty. There was low-fat yoghurt and kale juice in there, but Joe didn’t consider them to be food.

‘Mum!’ yelled Joe. But there was no reply. Joe assumed Mum was looking at a particularly engrossing dinosaur bone. He opened the pantry and sighed. There wasn’t much there either, except for a half-empty jar of olives. That would see him through until dinner. He opened the jar and wandered back to the living room.

‘Mum!’ yelled April. ‘Fin called me an idiot!’

‘No,’ said Fin. ‘I called you an idiot savant. In that context the word “idiot” is just an adjective. “Savant” is actually a compliment. It means “to be unnaturally good at something”.’

‘You said she was good at something?’ asked Joe. This was unusual. Fin was thirteen and April was twelve. They were, in fact, only eleven months apart. So for one month of the year they were technically the same age. And in all their lives since they had learned to speak, Fin and April had never said anything nice to each other. Not once.

‘He said I was an “idiot savant”,’ explained April, ‘at being a pain in the neck.’

‘It’s true,’ said Fin. ‘It is your one freakish talent.’

‘Mum!’ bellowed April again. Their mother didn’t have many rules, and the few rules she did have were rarely enforced. But she was adamant that they should not call each other ‘idiot’ or ‘stupid’, so April knew if she presented her argument well, she might get Fin in trouble.

‘If you dob me in,’ said Fin, ‘I’ll tell her what you did at lunchtime.’

‘I didn’t do anything at lunchtime,’ said April.

‘You wrestled Michael Harrigan to the ground,’ said Fin.

Now April rolled her eyes. ‘He loved it,’ she said, tucking her wavy dark hair behind her ear.

‘You d-did promise not to wrestle anymore,’ Joe reminded her.

‘The headmaster made you sign a contract saying you wouldn’t,’ Fin added.

‘I didn’t hurt Michael,’ said April.

‘You tore his shirt,’ said Fin, with his characteristic irritating accuracy.

‘He should learn to sew,’ April retorted. ‘It’s an important life skill.’

‘Fine,’ said Fin. ‘Then you won’t mind me telling Mum about it. Mum!’

‘You are the worst!’ said April, clenching her fists. If she was about to get in trouble for wrestling, she might as well do some more wrestling to make it worthwhile.

‘Where is she?’ said Joe, looking at the ceiling.

Their mother did not live in the ceiling. She had an office directly above the kitchen. Normally if they yelled and screamed long enough, they would hear their mother’s chair slide back as she got up and started down the stairs so she could shout at them to be quiet. But there were no sounds from above.

‘Did she say she was staying late at the museum?’ asked Joe.

Their mother was a palaeontologist. A very senior and well-respected one. But the thing about spending all day with a bunch of bones that are three hundred million years old is that nothing is ever really urgent. If it’s waited three hundred million years, it can wait another day. So their mother was very rarely late home, unless she accidentally got stuck in a lift or forgot her pass to get out of the car park. Which she did with surprising regularity. If you can’t keep track of your own house key, remembering a pass card is going to be pretty difficult too.

‘Maybe she got lost again,’ said April.

Their mother often got lost, particularly in shopping centres and shopping centre car parks. But she would usually just get a taxi home, pick up the kids and get them to help her find the car.

Joe looked at the answering machine next to the telephone. The light wasn’t flashing. There were no messages. She would have left a message if she was delayed.

‘She’s probably fallen asleep,’ said Fin. He went over to the staircase and bounded up the stairs two at a time. ‘It was pancakes for breakfast. That always makes her sleepy.’

They heard Fin throw open the office door.

‘Mum?’ he called, but there was no answer. Joe and April heard Fin looking in the other rooms upstairs. ‘She’s not here.’

‘I’ll check the shed,’ said Joe, trudging towards the back door.

‘Why? Do you think she decided to mow the lawn?’ asked April sarcastically. Their mother had never mowed the lawn. She didn’t understand the western cultural obsession with short grass. Some of their more zealous neighbours had pleaded with her to let them do it, saying that long grass encouraged snakes. But their mother said she liked snakes. A very low percentage of them were venomous, and they lived 2.3 kilometres from the nearest hospital. So even if one of them was bitten by a venomous snake, they would easily be able to access antivenom in time.

It only took Joe a few seconds to cross their small yard to the tiny shed where their mother kept things she didn’t use very often, like the vacuum cleaner and the ironing board. Mum wasn’t there. Joe came back, shaking his head. ‘Where could she b-b-be?’

Even April was starting to get concerned and generally she didn’t stop being angry long enough to be concerned about anything other than herself.

Pumpkin ran to the front door and started barking.

Fin jogged back down the stairs. ‘What’s he barking about now?’

‘The struggles of indigenous people in Papua New Guinea,’ said April.

Fin looked at her, confused.

‘As if we know why he’s barking!’ snapped April. ‘I don’t have dog ESP.’

‘True, how can you have Extra-Sensory Perception when you barely have regular perception,’ agreed Fin.

That was the straw that broke the camel’s back. April launched herself at Fin, grabbing him by the collar and wrenching him sideways to pull him off his feet. But twelve years of living with April had taught Fin a thing or two about self-defence tactics. He grabbed April’s wrists and dropped his weight on them so as he fell he brought her down too. April was just about to put Fin in a headlock and start administering noogies when there was an almighty BANG!

Their front door exploded inwards. Splintered wood flew everywhere and a stocky, black-clad figure wearing a full face mask burst into the room. The children found themselves looking down the barrel of a handgu

n.

‘Oh, it’s you,’ said the gunwoman, in an unexpectedly familiar feminine voice. She holstered the gun and pulled off her face mask.

‘Professor M-M-Maynard?’ exclaimed Joe. ‘Is that you?’

Now I must pause to explain a few things. Joe recognised this gunwoman because Professor Maynard was their mother’s boss. Joe, Fin and April’s mother was a very dowdy middle-aged woman. She wore frumpy, practical clothes, cheap thick-framed glasses and often forgot to brush her hair for several weeks at a time. So to them, their mother’s boss was frumpiness squared. She was just like their mother only more so, and older. She was the type of woman you’d expect to absentmindedly offer you the used tissue she’d pulled out of her sleeve cuff, not the type of woman you’d expect to burst into your home dressed like a ninja and brandishing a weapon.

‘Yes, I’m afraid it is me,’ said Professor Maynard. ‘Terribly sorry about that. It can’t be much fun for you to have an old lady waving a taser at you when you should be doing your homework.’

‘That’s a taser?’ asked Fin. ‘It looks a lot like a real gun.’

‘Don’t be a silly sausage,’ said Professor Maynard. ‘It would totally be against the rules to point a gun at children. But they make our tasers look like guns so they’re more terrifying.’ She got the taser out again. ‘See for yourself.’ Professor Maynard pulled the trigger and blasted the potted aspidistra that sat in the corner of the living room. The plant hissed and juddered as several thousand volts of electricity flooded through it.

‘I think I’d rather get shot,’ said Fin, as the leaves of the plant turned brown, then black and then started to singe.

The Final Mission

The Final Mission Stuck in the Mud

Stuck in the Mud Near Extinction

Near Extinction Bitter Enemies

Bitter Enemies No Rules

No Rules The Mystery of the Squashed Cockroach

The Mystery of the Squashed Cockroach The Plot Thickens

The Plot Thickens Nanny Piggins and the Accidental Blast-off

Nanny Piggins and the Accidental Blast-off Friday Barnes 2

Friday Barnes 2 Nanny Piggins and the Pursuit of Justice

Nanny Piggins and the Pursuit of Justice Nanny Piggins and the Race to Power 8

Nanny Piggins and the Race to Power 8 Nanny Piggins and the Wicked Plan

Nanny Piggins and the Wicked Plan Nanny Piggins and the Daring Rescue 7

Nanny Piggins and the Daring Rescue 7 Friday Barnes 3

Friday Barnes 3 Danger Ahead

Danger Ahead Nanny Piggins and the Runaway Lion

Nanny Piggins and the Runaway Lion The Adventures of Nanny Piggins

The Adventures of Nanny Piggins