- Home

- R. A. Spratt

Bitter Enemies Page 10

Bitter Enemies Read online

Page 10

‘Ah-hah!’ said Melanie. ‘Even the Headmaster admits he doesn’t care about PE.’

‘I need you to come with me right now,’ said the Headmaster. ‘Sergeant Crowley has asked to see us both.’

Friday dropped her lacrosse stick and scurried up the grass bank to the car. This sounded much more intriguing than another fifty minutes of watching other people hurl a ball about. Melanie climbed into the back seat beside her. The door had barely swung closed before the Headmaster gunned the accelerator and they took off.

‘I thought there was a ten kilometre per hour speed limit within school grounds,’ said Friday, hurrying to get her seat belt on before the Headmaster slammed into one of the many statues or garden features that littered the school grounds.

‘Who am I going to get in trouble with?’ said the Headmaster. ‘I’m the headmaster.’

‘You’ll probably get in trouble with the parents of the child you hit if you don’t slow down,’ said Melanie.

A group of year 7s walked down the library staircase and narrowly avoided becoming roadkill as the Headmaster whizzed past.

‘What happened?’ asked Friday, as the Headmaster pulled out onto the school driveway and sped towards the main road.

‘There’s been some trouble in town,’ said the Headmaster. ‘I don’t know much more, except that it involves Mr Novokavic.’

‘Why did they ask for me?’ said Friday.

‘It must be something Sergeant Crowley can’t figure out,’ said Melanie.

‘Perhaps how to tie his shoes,’ muttered the Headmaster.

‘That’s not very kind,’ said Melanie.

‘He interrupted my morning tea!’ said the Headmaster. ‘I’m not feeling very kind.’

‘Are we meeting him at the police station?’ asked Friday.

‘No,’ said the Headmaster. ‘The jewellery shop.’

‘Perhaps he’s going to buy us a present,’ said Melanie. ‘Daddy always likes taking me to jewellery shops.’

‘From his large physique and the frequent dusting of pastry crumbs on his clothes, I deduce Sergeant Crowley prefers to spend his disposable income on meat pies and high carbohydrate beverages.’ said Friday. ‘If he wants to meet us at the jewellery shop there must be a more sinister reason.’

The Headmaster’s BMW skidded to a halt outside the jewellery shop an impressive twelve minutes later. Friday knew this because she measured the time with her watch.

‘Given that the school is twenty-two kilometres from town and the speed limit is sixty kilometres per hour, you must have violated the traffic laws to get here in twelve minutes,’ said Friday.

‘Perhaps I passed through a wormhole and it got me here quicker,’ said the Headmaster.

‘Good one, Headmaster,’ said Melanie. ‘Impressive use of quantum physics in your comeback.’

‘I can see how that would be amusing to someone whose only source of information about physics is from watching science fiction television shows,’ said Friday. ‘So I won’t explain to you how wrong you actually are.’

The jewellery shop had the ‘closed’ sign hanging in the door, but the Headmaster pushed it open anyway. They entered to find the sergeant writing in his notebook. Mrs Gerrard, the very irritated looking proprietor of the shop, was glaring at Mr Novokavic as he sat in a chair singing nursery rhymes to himself.

‘Mary had a can of spam, can of spam, can of spam, Mary had a can of spam, and her face was made of snow,’ he chanted happily to himself. He looked dishevelled and a bruise was swelling under his left eye, but he was in good spirits.

‘Do you think he knows he’s getting the words wrong?’ Melanie whispered to Friday.

‘I defy anyone who has ever attended preschool to escape without knowing that Mary in fact had a little lamb,’ said Friday. ‘They certainly spent enough time going over the subject on the three days that I attended.’

‘I don’t see why you’ve got them down here,’ snapped Mrs Gerrard. ‘This is an open and shut case. I want to press charges.’

‘Yes, I know,’ said Sergeant Crowley. ‘You’ve made that abundantly clear. But in the absence of family, the Headmaster is the person most directly responsible for Mr Novokavic. If he is impaired, someone will need to assume power of attorney so that we can proceed.’

‘What happened?’ asked the Headmaster.

‘He robbed my shop,’ said Mrs Gerrard. ‘He stole a very valuable gold watch.’

‘Who did?’ asked Mr Novokavic, still in a singsong voice. ‘He sounds like a naughty boy. He’ll get in trouble with nanny when she finds out.’

‘You stay there, sir,’ said Sergeant Crowley. He guided Friday and the Headmaster to the other side of the small shop and spoke to them in a whisper. ‘The facts are pretty straightforward, but it is all very peculiar. The last thing I need is this situation getting out of control. HQ is already breathing down my neck about not being able to find Mrs Thompson, so I want to run through the case with you to see if you can make sense of it.’

Friday nodded. She glanced over at Mr Novokavic. He was an eccentric old gentleman at the best of times, but he was strange now. ‘Where’s the watch he stole?’ asked Friday.

‘I’m not getting it out of the cabinet again while he’s in the room,’ said Mrs Gerrard, glaring at Mr Novokavic.

‘That’s fine,’ said Friday. ‘I’ll look at it through the glass.’ Mrs Gerrard pointed out the watch. It was an impressive piece. Mr Novokavic had excellent taste in stolen goods. Friday checked her own watch and saw that it displayed the correct time and date.

‘Run me through exactly what happened and in chronological order,’ said Friday.

‘According to Mrs Garrard, it was busy in here this morning,’ began the sergeant. ‘Saturday morning is their busiest time. There were customers making purchases, but also people picking up things that had been cleaned or watches that had had their batteries replaced or straps repaired. So there were a few different customers in the shop when Mr Novokavic entered.’

Friday glanced around the ceiling. ‘There are no CCTV cameras,’ she noted.

‘Actually, there are,’ said Sergeant Crowley. ‘Mrs Gerrard is used to repairing small things from working on watches. When they put the CCTV cameras in she didn’t want them to look unsightly, so she fitted them into three of the knick-knacks.

‘Objets d’art!’ snapped Mrs Gerrard. ‘They are not knick-knacks, they are objets d’art.’

‘Yes, sorry, ma’am,’ said Sergeant Crowley. ‘There is one in that Staffordshire flatback of a dog over there. Another in the grandfather clock in the corner and a third one pointing at the entrance, hidden in the spout of that Wedgewood teapot.’

‘So there is video footage of the whole thing?’ asked Friday.

‘Yes,’ said Sergeant Crowley. ‘Clear as day. Mr Novokavic came in and looked around. Mrs Gerrard was showing a tray of gold wristwatches to another gentleman. When she turned her back to fetch a resized ring for a young couple, Mr Novokavic slipped off his own watch and swapped it with a watch on the tray.’

‘Then Mrs Gerrard noticed and called you?’ asked Friday.

‘No,’ said Sergeant Crowley. ‘The shop was busy, the watches looked superficially similar and Mr Novokavic didn’t leave immediately. Bold as brass he stood there, adjusting the time and date before he said goodbye and sauntered out.’

‘So how did he get back here?’ asked Friday.

‘Mrs Gerrard noticed the swapped watch a minute later,’ said Sergeant Crowley.

‘It was a cheap knock-off from Bangkok,’ snapped Mrs Gerrard. ‘They’d misspelled Rolex.’

‘She immediately checked the video footage,’ said Sergeant Crowley, ‘and soon discovered who the culprit was.’

‘Then she called you?’ asked Friday.

‘No, I wish she had,’ said Sergeant Crowley. He looked meaningfully at Mrs Gerrard.

‘A woman has the right to defend her property!’ said Mrs Gerrard.

‘Yes

,’ said Sergeant Crowley. ‘It would have been defence if you’d done it in the store. But chasing a ninety-one-year-old man down the high street and crash-tackling him in front of hundreds of witnesses is what the courts like to call “disproportionate use of force”.’

‘Excuse me if having a $5,000 watch stolen from under my nose makes me a little emotional,’ snapped Mrs Gerrard. ‘I’m a hard-working woman, doing my best to keep this small business afloat. I don’t appreciate being robbed.’

‘Yes, but if Mr Novokavic has dementia,’ said Sergeant Crowley, ‘as all the signs indicate he does …’

They turned and looked at Mr Novokavic. He was muttering nursery rhymes to himself again, ‘Baa baa black feet, have you any wool? Yes, sir, no sir, but I’ve got a great big bull …’

‘Then he will get off on account of diminished responsibility,’ said Sergeant Crowley, ‘and Mrs Gerrard could well end up facing charges of assault.’

‘What?!’ yelped Mrs Gerrard. ‘But he stole from me!’

‘In the eyes of the law, assault is a far greater crime,’ said the sergeant.

‘He has got quite a shiner,’ said Melanie, taking a good look at Mr Novokavic’s black eye. ‘That won’t look good if his picture gets in the paper.’

‘And several members of the public did take pictures with their smartphones,’ said the sergeant.

‘All right, that’s enough of that,’ said the Headmaster. ‘There is absolutely no need to get into all this. No-one needs to face the court, or the court of public disapproval. Mrs Gerrard has had her watch returned to her. Mr Novokavic has learned his lesson, and suffered retribution in the form of a black eye. Why don’t we call it quits, and all walk away pretending this never happened?’

‘But, Headmaster, you’re ignoring several pertinent –’ began Friday.

‘Silence,’ ordered the Headmaster. ‘If you don’t want to be expelled, although it would be hard to expel a student who technically isn’t enrolled, then you should choose this moment to be silent. We will settle this difference, and anything further you have to say you can say at school.’

‘No, sir, you really have to –’ Friday tried again.

‘Get out!’ barked the Headmaster. ‘Go and stand on the pavement, while the grown-ups sort this out. Go!’

Friday and Melanie left the shop.

‘I can’t believe he didn’t want to know all the facts,’ said Friday.

‘Sometimes facts can be deceptive,’ said Melanie, as she pressed her nose to the window and peered back into the shop.

‘What are you doing?’ asked Friday.

‘Lip reading,’ said Melanie.

‘I didn’t know you could do that!’ said Friday, coming over to peer in as well.

‘I don’t know if I can do it accurately,’ said Melanie, ‘because if you can’t hear what someone is saying, then you’ve got no way of knowing if you are right. But I’ve always thought I knew how to lip read.’

‘What are they saying?’ asked Friday.

‘The Headmaster is grovelling to Mrs Gerrard,’ said Melanie.

‘Really?’ asked Friday.

‘He’s looking humble and deferential. He’s actually clasping his hands together like he’s begging,’ said Melanie.

‘But can you tell what he’s saying?’ asked Friday.

‘So, so sorry. Terribly distressing for you. Would you accept a small gift as compensation?’ lip read Melanie.

They could see the Headmaster holding out a large bundle of cash at this point. But Mrs Gerrard didn’t reach out to take it. She started to speak.

‘What’s Mrs Gerrard saying?’ asked Friday.

‘She says … she thinks the Headmaster can do better,’ lip read Melanie. ‘She wants a thumbtack.’

‘What?’ said Friday.

‘Actually, maybe she said “contract”,’ said Melanie.

‘That would make more sense,’ said Friday.

‘She wants a contract for all the trophy engraving and polishing business from the school,’ continued Melanie. ‘A fifty-year exclusive contract for the school’s business.’

‘She’s a smart woman,’ said Friday. ‘That would be worth a lot more than a bundle of cash.’

The Headmaster reached out his hand. Mrs Gerrard smiled a grim smile, then reached out and shook it.

‘I guess that’s all over then,’ said Melanie.

‘I don’t like it,’ said Friday. ‘Not one little bit. I don’t believe Mr Novokavic has dementia. And if he’s faking that, what is he up to?’

‘How do you know he’s faking?’ asked Melanie.

‘He hasn’t done his research properly,’ said Friday. ‘He’s reciting nursery rhymes but getting the words wrong.’

‘But people with dementia do that,’ said Melanie. ‘They can’t remember things.’

‘They can’t remember things they have learned recently,’ said Friday. ‘It is the most recently formed memories that go first. A nursery rhyme learned in early childhood would be retained the longest.’

‘Maybe he has severe dementia right away,’ said Melanie.

‘That is statistically unlikely,’ said Friday. ‘And it’s not the only thing that doesn’t fit with the pattern of symptoms.’

‘What do you mean?’ asked Melanie.

‘When he put on the stolen watch he adjusted it. I had a look and he did it accurately. He got the time and date right,’ said Friday. ‘Even people without dementia have trouble remembering the date. For people with dementia that is one of the first things to slip. He wouldn’t know the day of the week and the date. And even if he did, people with dementia have poor fine motor skills. They struggle with something as large as a faucet on a kitchen sink. A little knob on a watch would be impossible for them to use.’

‘So he’s faking it?’ said Melanie.

‘I think so,’ said Friday. ‘But the question is – why?’

The bell above the door tinkled as the Headmaster led Mr Novokavic out. ‘In the car,’ the Headmaster snapped at the girls as he ushered his predecessor past.

‘Oh well,’ said Melanie. ‘At least Mr Novokavic will still be able to teach. He may be going potty, but he still talks more sense than Mr Maclean.’

They all got in the car and drove back to school, while the Headmaster gave Friday and Melanie a long lecture on how they must never mention this incident to anybody.

School was dull for the next few days. Neither Dr Wallace nor Mr Novokavic were teaching. Dr Wallace was apparently too sick to leave her rooms and Mr Novokavic just wandered the gardens down by the swamp, mumbling random thoughts to himself like King Lear (at the end of the play when he’s gone mad, not the beginning of the play where he’s all bossy).

There was so much suspicious behaviour that Friday longed to investigate, if the Headmaster would just let her.

The only excitement came from avoiding Harrison Abotomey. Now that his feelings had been revealed, he had taken to leaving gifts outside Friday and Melanie’s room. Sometimes, Friday would step outside and discover a bunch of flowers, which was quite nice really. But then another morning he would leave her a bowl of banoffee pudding, her favourite dessert, and it was just creepy that he knew that. So Friday had taken to suddenly leaping out of windows and diving through flowerbeds to try and shake him. But Abotomey had memorised her class schedule so she could never avoid him for long. She was always catching glimpses of him watching her from a distance.

This was making things difficult with Ian. He had reverted to his old snarky self. Friday could not understand why Ian was angry with her, or why he cared what Abotomey thought. She refused to entertain Melanie’s constant comments about romance. It just did not make logical sense. Friday tried analysing the whole situation using rigorous scientific reasoning, but the only conclusion she was able to reach was that boys were weird.

And so, one morning, Friday was sitting slumped at her desk at the back of her chemistry lesson. She knew Abotomey was hiding in the bushes outs

ide and she didn’t want him to be able to see her. Suddenly the class was interrupted by a knock at the door.

‘What is it?’ asked Mr Davies, pausing in mid-equation.

‘The Headmaster wants to see Friday in his office,’ puffed the messenger.

‘Which one?’ asked Melanie. ‘We seem to have an excess of headmasters at the moment.’

‘Except for the one who is missing,’ said Friday.

‘Good point,’ said Melanie.

‘The Headmaster,’ emphasised the messenger.

‘Finally!’ said Friday, leaping to her feet. ‘He is going to accept my help in the Case of the Missing Headmistress.’

Four minutes later, Friday enthusiastically burst into the Headmaster’s office, closely followed by Melanie.

‘Where shall we start?’ asked Friday. ‘Do I have a budget to send away for DNA testing?’ She looked around and was perplexed to realise that the Headmaster wasn’t actually in his office.

‘He’s not here,’ said Friday.

‘Oh no,’ said Melanie. ‘Does that mean another one has gone missing?’

‘I’m right here, you imbeciles,’ said the Headmaster grumpily, as his head appeared above the edge of his desk.

‘What are you doing under your desk?’ asked Melanie. ‘I can understand why someone else would hide under your desk to avoid you, but you hardly need to do that.’

‘I can’t find my aspirin,’ said the Headmaster. ‘I’ve looked everywhere. It’s maddening.’

‘Why don’t you ask Miss Priddock if she’s got some?’ suggested Friday.

‘Leave that woman out of it,’ said the Headmaster, rubbing his arm angrily.

‘I’m sure the school nurse would have aspirin,’ said Melanie. ‘She’d be a pretty poor nurse if she didn’t.’

‘I don’t want every infernal member of staff gossiping about my ailments,’ said the Headmaster.

‘Have you tried lying down in a dark room with a damp cloth over your face?’ asked Friday. ‘I believe that’s good for headaches too.’

‘I did not summon you here for your infuriating know-it-all comments,’ said the Headmaster. ‘So less of the chit-chat and just find my darn aspirin.’

The Final Mission

The Final Mission Stuck in the Mud

Stuck in the Mud Near Extinction

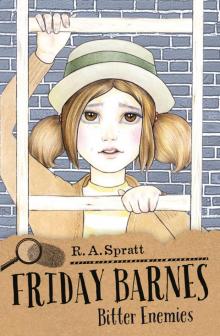

Near Extinction Bitter Enemies

Bitter Enemies No Rules

No Rules The Mystery of the Squashed Cockroach

The Mystery of the Squashed Cockroach The Plot Thickens

The Plot Thickens Nanny Piggins and the Accidental Blast-off

Nanny Piggins and the Accidental Blast-off Friday Barnes 2

Friday Barnes 2 Nanny Piggins and the Pursuit of Justice

Nanny Piggins and the Pursuit of Justice Nanny Piggins and the Race to Power 8

Nanny Piggins and the Race to Power 8 Nanny Piggins and the Wicked Plan

Nanny Piggins and the Wicked Plan Nanny Piggins and the Daring Rescue 7

Nanny Piggins and the Daring Rescue 7 Friday Barnes 3

Friday Barnes 3 Danger Ahead

Danger Ahead Nanny Piggins and the Runaway Lion

Nanny Piggins and the Runaway Lion The Adventures of Nanny Piggins

The Adventures of Nanny Piggins