- Home

Page 3

Page 3

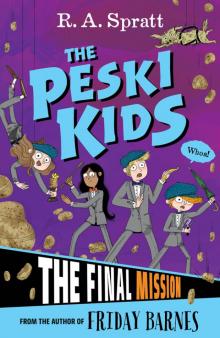

The Final Mission

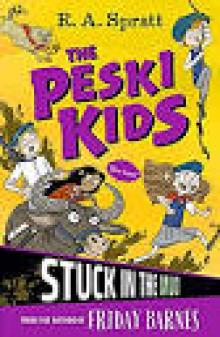

The Final Mission Stuck in the Mud

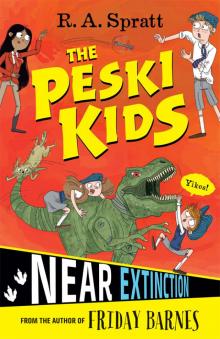

Stuck in the Mud Near Extinction

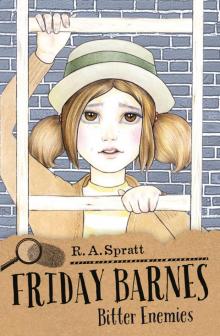

Near Extinction Bitter Enemies

Bitter Enemies No Rules

No Rules The Mystery of the Squashed Cockroach

The Mystery of the Squashed Cockroach The Plot Thickens

The Plot Thickens Nanny Piggins and the Accidental Blast-off

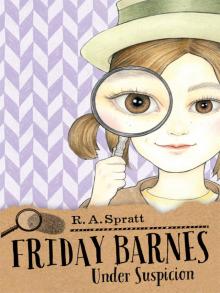

Nanny Piggins and the Accidental Blast-off Friday Barnes 2

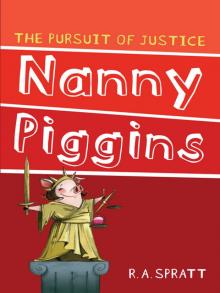

Friday Barnes 2 Nanny Piggins and the Pursuit of Justice

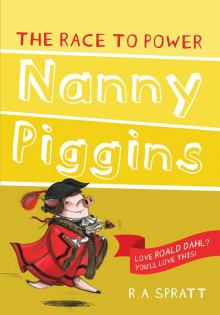

Nanny Piggins and the Pursuit of Justice Nanny Piggins and the Race to Power 8

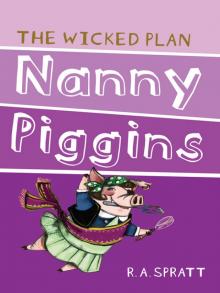

Nanny Piggins and the Race to Power 8 Nanny Piggins and the Wicked Plan

Nanny Piggins and the Wicked Plan Nanny Piggins and the Daring Rescue 7

Nanny Piggins and the Daring Rescue 7 Friday Barnes 3

Friday Barnes 3 Danger Ahead

Danger Ahead Nanny Piggins and the Runaway Lion

Nanny Piggins and the Runaway Lion The Adventures of Nanny Piggins

The Adventures of Nanny Piggins