- Home

- R. A. Spratt

Bitter Enemies Page 5

Bitter Enemies Read online

Page 5

‘In your day,’ said the woman, ‘they were still using horses and carts.’

‘Is he all right?’ asked the Headmaster.

‘Well, he’s breathing, and there’s no blood,’ said the woman. ‘But I suppose there could be brain damage.’

‘Miss Priddock, call an ambulance!’ bellowed the Headmaster.

Miss Priddock was standing some distance away outside the admin block but they all heard her wail as she scurried back inside. She was being yelled at more today than she had since she turned fifteen and had her braces off and everyone realised she was fabulously beautiful.

‘It’s odd that he was out here,’ said Friday, looking around. ‘Everyone else was in class. How did he come to be on the driveway? You should roll him on his side so he doesn’t choke on his own vomit.’

‘He isn’t vomiting,’ said the Headmaster.

‘Not yet,’ said Friday, ‘but vomiting is a symptom of concussion.’

‘Plus, Mrs Marigold has been getting very experimental with the cooking lately,’ said Melanie. ‘I’m not convinced that the sashimi she made for lunch was really sashimi. I think it was meant to be roast salmon but she was just too fed up to cook it.’

‘She’s on a diet,’ said Friday.

‘How do you know?’ asked Melanie.

‘There were several clues – irrational bouts of rage, the half-hearted cooking,’ said Friday. ‘But the main indicator was that she’s lost fifteen kilos in body weight.’

‘Poor woman,’ said Melanie.

The Headmaster carefully rolled the stricken figure onto his side, and as soon as they saw his face, they all recognised him.

‘Parker!’ exclaimed Friday.

‘This boy is known to you?’ demanded the elderly man.

‘He is one of our more … “special” students,’ said the Headmaster. ‘But why on earth would he step in front of a car?’

‘Vandalism, that’s what I call it,’ said the elderly man. ‘Look at the mess he’s made of my paintwork.’

Everyone looked at the bumper. There was a mark on it but it wasn’t a dent.

‘That’s bird poo,’ said Friday.

‘The devil,’ said the elderly man. ‘He must have smeared it on there as he hit the car.’

‘To be fair,’ said the plump woman, ‘the boy did seem to come from nowhere.’

‘But were you looking, Mrs Thompson?’ asked Friday.

‘I beg your pardon,’ said the woman. ‘Do I know you?’

‘We are waiting for four former headmasters to arrive,’ said Friday. ‘Dr Wallace and Colonel Hallett are already here. From the extensive amount of time I am obliged to sit outside the Headmaster’s office reading the honour boards, I know that the other two surviving former headmasters are Mrs Thompson and Mr Novokavic.’

‘But why would you suggest that I wasn’t looking?’ said Mrs Thompson. ‘I have to look when Horace is driving, so I can brace for impact. He’s the worst driver I’ve ever ridden with.’

‘Why don’t you drive?’ asked Melanie.

‘Oh, I don’t drive,’ said Mrs Thompson. ‘In my day it was considered unladylike.’

‘Then surely you are a worse driver than Mr Novokavic,’ said Friday.

‘Friday, please don’t go out of your way to insult people,’ said the Headmaster. ‘We have to help Parker.’

‘There’s nothing we can do for a head injury,’ said Friday. ‘Unless we think he’s bleeding into his cranium, then someone should find Mr Pilcher and borrow his power drill so we can drill a hole into Parker’s skull to relieve the pressure.’

‘I’ll go,’ said Binky. He’d already taken off running a couple of paces.

‘No!’ exclaimed the Headmaster. ‘No-one is drilling into anyone’s skull, not on school grounds, not while I’m the one who has to fill out the occupational health and safety forms.’

‘The mystery is – why was Parker out here?’ said Friday, looking about. ‘He should have been in class. And where did he come from? The automatic sprinklers were on this morning, the grass is still covered in droplets of water. We would see footprints if he had walked across the lawn. There are no footprints in the flowerbed. And he can’t have come through the admin building or someone would have seen him.’

‘Only Miss Priddock,’ said Melanie, ‘and she’s not very observant. Especially when she’s crying about being yelled at.’ Melanie looked meaningfully at Colonel Hallett.

‘Maybe he came up the driveway,’ said Binky. ‘You don’t leave footprints on a driveway.’

‘But he can’t have been coming from that direction,’ said Friday. ‘We just had assembly on the other side of the quad. Besides, the gravel driveway is better than a burglar alarm. It’s so noisy when someone walks on the gravel he would have got in trouble.’

‘He had to come from somewhere,’ said the Headmaster.

Friday looked up. ‘Oh, I know where he came from.’ They were standing alongside the science block. ‘Whose classroom is up there on the second floor?’ asked Friday.

‘It was Miss Dayball last year, but we had to move some of the teachers around this term,’ said the Headmaster.

‘Is it Mr Spencer now?’ asked Friday.

‘How did you know?’ asked the Headmaster.

‘Because Parker is particularly afraid of Mr Spencer, ever since the time a dog literally ate his homework,’ said Friday.

‘I don’t think it helped that you brought poo to class to prove it was true,’ said Melanie.

‘A science teacher who doesn’t accept scientific evidence simply because it is stinky has a very poor attitude,’ said Friday.

‘So what are you suggesting happened?’ asked the Headmaster.

‘I think Parker was sitting in class waiting for his teacher to arrive, and when Mr Spencer turned up he panicked and jumped out the window,’ said Friday.

‘That’s ridiculous,’ said the Headmaster.

‘Yes, but it is the only solution that fits all the evidence,’ said Friday, ‘and Parker is ridiculous so it makes sense.’

‘It doesn’t change the fact that he’ll need to go to hospital for a brain scan,’ said the Headmaster.

‘Well, that’s up to you,’ said Friday, ‘but personally I doubt it’s necessary.’

‘He’s unconscious and he was hit by a car,’ said the Headmaster.

‘Well, he was hit by a car,’ agreed Friday, ‘but not very hard. The speed limit on school property is ten kilometres an hour and, given Mr Novokavic’s epic levels of pedanticalness and being a stickler for rules, I doubt he was exceeding that speed.’

‘Barely reaching it,’ agreed Mrs Thompson.

‘And Parker is not unconscious,’ said Friday.

‘What?!’ exclaimed the Headmaster. ‘But the boy hasn’t moved.’

‘Yes, but his breathing is all wrong,’ said Friday. ‘When you’re unconscious you breathe shallow, reedy breaths.’

Everyone leaned in to observe the depth of Parker’s breathing.

‘Also,’ continued Friday, ‘when you’re unconscious you don’t flinch when someone suggests drilling a hole into your head.’

‘He did that?’ asked Melanie.

‘Yes, you were all looking at me,’ said Friday, ‘because you were shocked by my suggestion. But I was watching Parker and he distinctly flinched.’

‘Well, he’s not flinching now,’ said Binky. ‘He’s very still. I couldn’t lie that still. Not without scratching my nose or something.’

‘We’ll soon see,’ said Friday. ‘I happen to know what paramedics do to check if someone is really unconscious. Does anybody have a pen?’

‘Are you saying you don’t have a pen?’ asked Melanie.

‘I suppose I do,’ said Friday, going through her cardigan pockets. ‘It just seemed more dramatic to ask if someone else had one.’

‘I’ve had quite enough drama here, thank you very much,’ said the Headmaster.

Friday found a biro, knelt down

next to Parker and picked up his hand. She lay the biro across the back of the fingernail on his index finger, then squeezed it into the nail hard.

‘Oww!’ wailed Parker as he sat up suddenly. ‘What did you have to do that for?’

‘I was just checking you were all right,’ said Friday. ‘Everyone was worried you had a brain injury.’

‘I’ve got a finger injury now,’ said Parker, shaking out his hand.

‘No, you don’t,’ said Friday. ‘It just hurts because you have lot of nerve endings in your fingertip. I haven’t damaged you.’

‘Parker, you get detention every day for a fortnight!’ railed the Headmaster. ‘How dare you jump out of your classroom window?’

‘And assault my car,’ said Mr Novokavic.

‘Yes, and another week for assaulting his car,’ added the Headmaster.

‘Aw,’ said Parker. ‘I didn’t realise the car was there when I jumped.’

‘But why on earth would you do something so idiotic?’ demanded the Headmaster.

‘I forgot how much I hate science,’ said Parker. ‘It was only when Mr Spencer walked in the classroom that it all came back to me. I had to get out.’

‘But you’re in fourth form,’ said the Headmaster. ‘You choose your own electives. Why don’t you pick other subjects? You could do history, geography, art … anything you like!’

‘Oh, I hate all of those even more,’ said Parker. ‘Don’t get me wrong, I like school. I’m just not keen on the actual studying. It’s really hard work for us less brainy fellows.’

‘I know,’ agreed Binky.

‘You can’t go round jumping out of second storey classrooms,’ said the Headmaster. ‘You could have broken a leg.’

‘I was hoping to, sir,’ said Parker. ‘A broken leg would definitely get me a night in hospital. I might even get to go home for a week if it was a compound fracture.’

‘I see you’ve allowed admissions standards to slip since my day,’ said Mr Novokavic. ‘I don’t understand how this boy could have passed the entrance exam.’

‘There is no entrance exam to get into Highcrest anymore,’ said the Headmaster.

‘Then how can you maintain standards?’ asked Mr Novokavic.

‘We charge four times more than what is reasonable,’ said the Headmaster.

‘This boy needs more physical activity,’ said Mrs Thompson. ‘Get him up at the crack of dawn for rugger drills. He won’t have the energy to jump out of windows then.’

‘The rugby master would complain to the union if I made him get up that early,’ said the Headmaster.

‘Wouldn’t have happened in my day,’ repeated Mr Novokavic, as he handed Binky a rickety old suitcase and started ambling towards the guest quarters. Binky hesitated for a moment.

‘You’re supposed to follow him with his bag,’ whispered Melanie.

‘Thanks, Mel,’ said Binky. ‘I wasn’t sure what was going on at all. I was still thinking about rugby drills.’ Binky hurried off after Mr Novokavic.

‘Since you are apparently unharmed, young man,’ said Mrs Thompson, handing Parker her suitcase, ‘you may carry my luggage.’ She swanned off with Parker following in her wake.

‘Who do they think is going to park this car?’ asked the Headmaster, indicating the Volvo that had been abandoned in the middle of the drive. ‘Do they think we have valet parking?’

‘Perhaps they did in their day,’ said Melanie.

‘Can you drive, Barnes?’ asked the Headmaster.

‘I’m only twelve,’ said Friday.

‘That doesn’t stop you doing most things,’ observed the Headmaster. ‘I suppose I had better do it myself.’ He got in the car muttering about how he’d really like to drive off to a distant holiday location where no-one could find him.

‘Poor Headmaster,’ said Melanie as he drove away. ‘Things haven’t got off to a good start.’

‘On the bright side, things can hardly get worse,’ said Friday.

‘You shouldn’t have said that,’ said Melanie.

Friday had entertained a slim hope that Dr Wallace would turn out to be a loveable old curmudgeon whose gruff exterior hid a heart of gold and a vocation to teach Friday everything she knew. This was not the case. Dr Wallace was definitely a curmudgeon, but not the loveable kind. She seemed to have little interest in education and a lot of interest in using the opportunity her new situation provided to use Friday as an unpaid servant. Dr Wallace had not been exaggerating when she said she was an early riser.

When Friday arrived at 5.45 am on the first morning, Dr Wallace had already laid out several tasks for her. It was almost as if she had got up an hour early to prepare all the work. To start, Friday had to polish her shoes and do her laundry. Dr Wallace had only been at the school for thirty-six hours, so Friday marvelled at how much laundry she had already created. She seemed to have spent an inordinate amount of time down by the swamp, judging from the mud on her shoes and trouser cuffs.

Friday was surprised to discover that Dr Wallace bought her shoes from the same discount department store that she did. But some intellectuals were eccentric about being excessively frugal. She knew a professor of astrophysics who never paid for clothes, instead he stole them from charity bins that he passed on the way home from work. And yet he also regularly splurged on buying caviar for all seventeen of his cats. Some people had strange financial priorities.

Once the cleaning and ironing was done, Friday had to get started on the paperwork. She had to arrange the day’s lesson prep, print out resource material, and alphabetise the student profiles for each of Dr Wallace’s classes. Friday had not realised that such a thing as ‘student profiles’ even existed. She was horrified to read her own.

Freitag (Friday) Barnes

12 years old

Academics high

Athletics low

Attitude poor

Troublemaker, stickybeak, know-it-all

‘Troublemaker?!’ exclaimed Friday. ‘That’s just not fair. I only ever solve problems.’

‘From what I’ve heard, you are the problem,’ said Dr Wallace crushingly.

Friday pouted. She was used to being reviled by the other students, and even disliked by many of the staff, but she wasn’t used to being held in contempt.

‘You’re here to act as my steward,’ said Dr Wallace, ‘not my conversational companion. I prefer silence in the morning. It’s good for self-discipline.’

Friday was running late by the time she was finally released and allowed to go to class herself.

‘Glad you could make it, Barnes,’ said Mr Maclean sarcastically. He didn’t like Friday because she knew more about geography than he did. To be fair, there were five-year-olds who knew more about geography than Mr Maclean. He wasn’t the most accomplished teacher.

‘It’s all right, sir,’ said Friday. ‘I already know how ocean currents work, how to read a topographical map and the ecosystem of a desert. I read this year’s syllabus over the weekend.’

‘I don’t know why you bother coming to class at all if you know everything,’ said Mr Maclean waspishly.

‘If I only attended classes where I didn’t know everything,’ said Friday, ‘I’d barely go to class at all.’

‘Except PE,’ said Melanie helpfully. ‘You’ve got a lot to learn there.’

‘True,’ agreed Friday, as she sat down.

‘Well, since you’re here, open your textbook to page –’ began Mr Maclean. But he never got to finish his sentence. There was an urgent knock at the door.

‘What now?’ demanded Mr Maclean.

Harvey opened the door.

‘I’ve got a message, sir,’ said Harvey, waving a note.

‘What is it?’ asked Mr Maclean, holding out his hand.

‘It’s not for you, sir,’ said Harvey. ‘It’s for Barnes.’

‘For goodness sake, Barnes!’ exclaimed Mr Maclean. ‘You treat this school like your own personal secretarial service.’

‘That’

s hardly fair,’ said Friday. ‘It’s the school that treats me as their personal in-house detective.’

Friday took the note and read it.

‘What does it say?’ said Melanie. ‘We’re all dying to know.’

‘You’re supposed to be dying to know about ocean flow,’ snapped Mr Maclean.

‘Come to the Headmaster’s office urgently,’ read Friday. ‘I’ve been framed. Ian.’

Melanie peered over her shoulder. ‘Just Ian? No love and kisses. No fondly, Ian, or yours truly, Ian?’

‘What’s going on, Harvey?’ asked Friday.

‘I don’t know,’ he replied. ‘Wainscott just grabbed me and asked me to give you that.’

Friday stood up and started packing the few things she’d had time to unpack.

‘You can’t leave!’ wailed Mr Maclean. ‘It isn’t the Headmaster who summoned you. It’s just your boyfriend.’

‘He’s not my –’ began Friday. But this time she was the one who didn’t get to finish her sentence.

‘He’s not my boyfriend!’ the whole class chanted. They had heard this many, many times before.

Friday just rolled her eyes as she slung her bag over her shoulder and headed for the door. Melanie followed after her. She hadn’t unpacked anything. She found it was easier to sleep slumped across the desk if there was no stationery in the way.

‘Don’t make a fuss, Mr Maclean,’ said Friday. ‘We all know you don’t really want me here with my irritatingly accurate answers and superior understanding of concepts.’

‘Just go,’ said Mr Maclean.

When they arrived at the Headmaster’s office, the door was open, so Friday walked straight in.

‘What’s going on then?’ she asked.

Ian was sitting on the chair in front of the Headmaster’s desk staring at the floor, and Colonel Hallett was pacing back and forth. She had clearly caught him mid-rant.

‘How dare you interrupt!’ yelled Colonel Hallett. ‘Wait outside!’

‘No,’ said Ian, standing up. ‘I’ve called her here to act as my legal representative.’

‘You’re a thirteen-year-old school boy, you don’t get legal representation,’ snapped Colonel Hallett.

The Final Mission

The Final Mission Stuck in the Mud

Stuck in the Mud Near Extinction

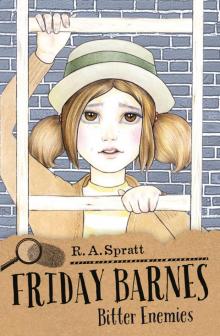

Near Extinction Bitter Enemies

Bitter Enemies No Rules

No Rules The Mystery of the Squashed Cockroach

The Mystery of the Squashed Cockroach The Plot Thickens

The Plot Thickens Nanny Piggins and the Accidental Blast-off

Nanny Piggins and the Accidental Blast-off Friday Barnes 2

Friday Barnes 2 Nanny Piggins and the Pursuit of Justice

Nanny Piggins and the Pursuit of Justice Nanny Piggins and the Race to Power 8

Nanny Piggins and the Race to Power 8 Nanny Piggins and the Wicked Plan

Nanny Piggins and the Wicked Plan Nanny Piggins and the Daring Rescue 7

Nanny Piggins and the Daring Rescue 7 Friday Barnes 3

Friday Barnes 3 Danger Ahead

Danger Ahead Nanny Piggins and the Runaway Lion

Nanny Piggins and the Runaway Lion The Adventures of Nanny Piggins

The Adventures of Nanny Piggins